Published ten years ago, Piers McGrandle’s biography of Trevor Huddleston gives another insight into the rule of law in operation when applied to those with a reputation deemed valuable enough to protect. [Scroll down for Chapter 24: ‘Collapse’ pp 151 – 160 at the bottom of this post]

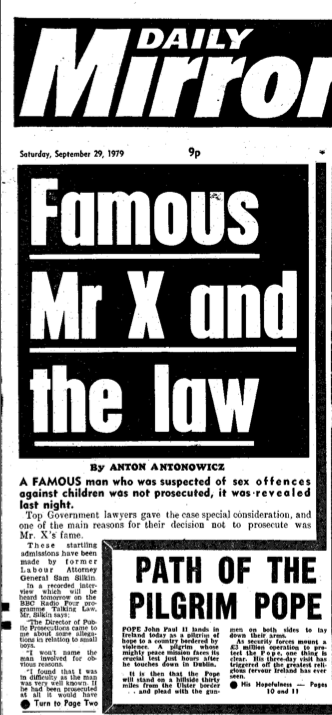

In September 1979 on BBC Radio 4’s Talking Law programme, Labour Attorney General Sir Samuel Silkin (under Wilson and then Callaghan during 1974 – 1979) referred to to one case in particular, admitting that special consideration had been given to the plight of the famous (see p. 156 Trevor Huddleston: Turbulent Priest, Pier McGrandle below):

“I won’t name the man for obvious reasons. The Director of Public Prosecutions came to me about some allegation in relation to small boys. Although it was entirely within his province, it was something which he could ask the Attorney whether to prosecute or not, he said.

I found that I was in difficulty as the man was very well known. If he had been prosecuted at all it would have ruined his career and his influence. Within the DPP’s department everyone though he would be acquitted though there was clearly evidence.”

This view chimes in tone and content with Sir David Napley’s later 1981 press-reported defence of his client, Sir Peter Hayman, and the decision of Attorney general Sir Michael Havers and DPP Sir Thomas Hetherington in deciding not to prosecute (ignoring for the moment Havers’ tortuous attempt to gloss the Post Office Act with some casuistic reasoning applied to what constitutes ‘solicitation’).

Napley asserted a ‘customary factor’ existed for prosecutors to consider when exercising their discretion whether to prosecute or not, namely:

“whether the indirect punishment and hardship which a defendant may suffer is likely to be so disproportionate to the severity of the alleged offence and to any penalty imposed by a court that it would be unjust to prosecute.” [The Questions Unanswered in the Hayman case, The Times, Ronald Butt, 26 March 1981]

If this was an accurate representation as to how prosecutorial discretion was exercised in relation to those with reputations considered worth protecting, it suggests we’ve been making a mockery of Dicey’s second tenet of the rule of law for some time – “none shall be above it” – since it divides the rule of law into applying to those with fame and those without. And the rule of law, divided, is by definition, no longer the rule of law. It ceases to exist conceptually.

There is an undeniable suggestion of a prevailing legal view at the time circulating amongst the government’s Law Officers and highly regarded lawyers such as Napley (former President of the Law Society) that those with fame apparently bear an additional burden for the prosecution to consider – a reputation that could be lost. For the rest of us mere mortals, our everyday ignominy would mean prosecutorial discretion doesn’t need to weigh fame or reputation in the balance.

When Napley’s customary factor is applied to exercising prosecutorial discretion in the case of a well-known accused like Hayman, the severity of the alleged offence is positioned inversely and directly on the scales in opposition to the size or magnitude of the accused’s celebrity or reputation (and it must be emphasised potential, but not conclusive, loss thereof as a result of a mere allegation, let alone a not guilty verdict following prosecution) in addition to any penalty imposed by a court. Therefore, the mere fact a well-known accused has a reputation to lose can weigh disproportionately in their favour, acting as a cloak or shield from due process or prosecution. In a double whammy, the more socially taboo the nature of the crime alleged, the more potential damage to a reputation if prosecuted unsuccessfully, despite and especially where the allegations relate to child abuse related offences.

However, considering the after-effects of prosecution for sexual abuse of young boys in context of the following:

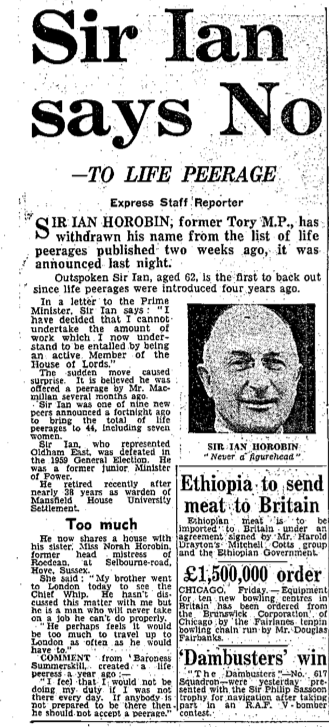

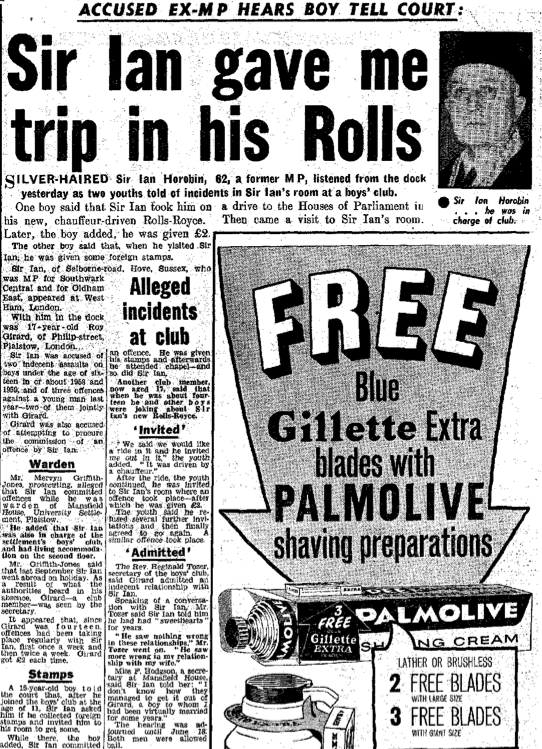

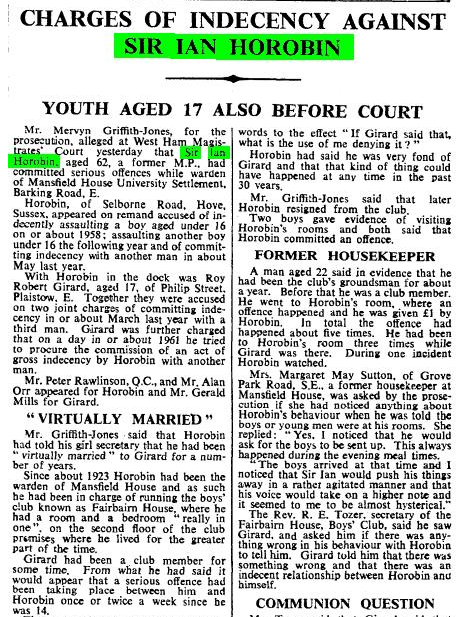

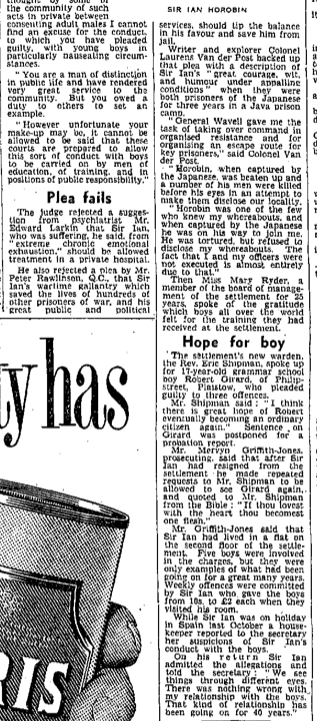

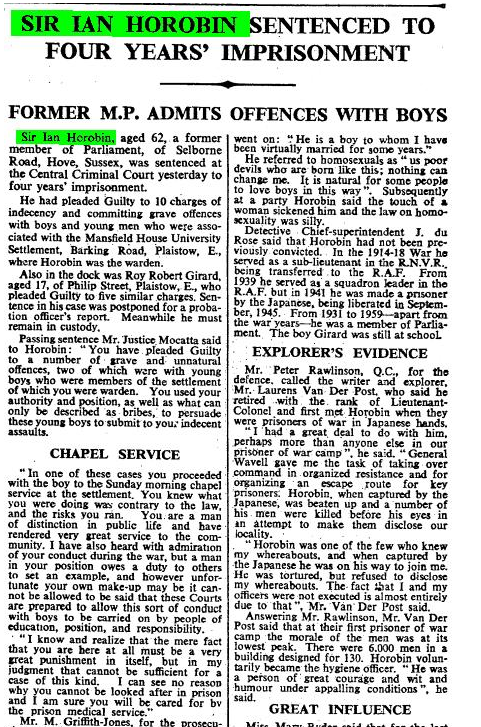

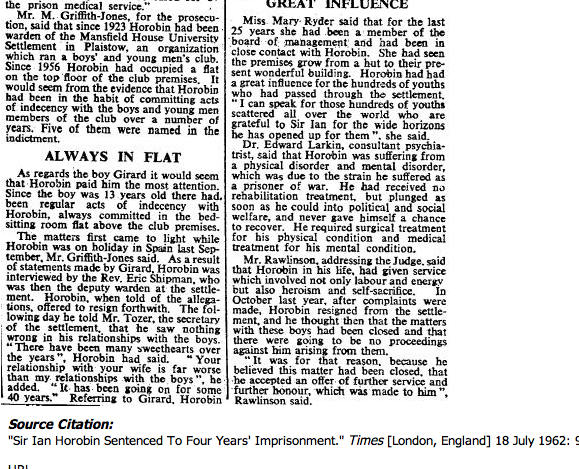

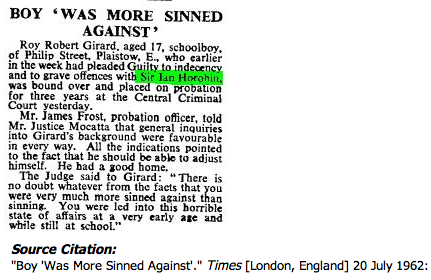

(1) Sir Ian Horobin MPs (Con: Oldham East) ebullient bounceback from his 1962 conviction by publishing a poetry anthology with a foreword by John Betjeman in 1973 (nb. the curiously mournful comment ‘Even the elms are dead’), written during post-prison recuperation in Tangiers where boys could be preyed upon; and

(2) Charles Hornby’s successful application for a gun licence just over six months after his release from prison for his part in the Playland Piccadilly Amusement Arcade Trial of 1975, granted by a Recorder who didn’t need to recuse themselves over a dinner party or two,

it appears the ill-effects of ‘loss of reputation’ can be very much countered by one’s well-placed friends rallying around so that life and even reputations may resume post-prosecution.

1974: Trevor Huddleston and John Junor’s spiked article

As a priest in Johannesburg Trevor Huddlestone had challenged the government’s apartheid policy during the 1950s becoming a leading light in the anti-apartheid movement. But by 1974 Trevor Huddleston, was an Anglican ‘suffragan’ Bishop of Stepney in the Diocese of London, and member of the Anglican religious order of the Community of the Resurrection since 1941 (Mirfield, West Yorkshire).

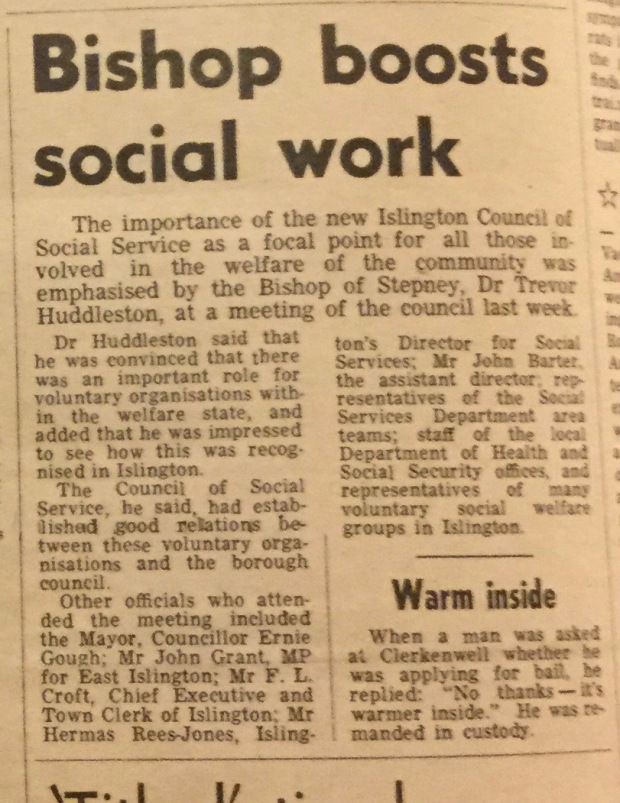

In 1970 Dr Huddleston found time to launch Islington’s Council of Social Service, a voluntary body established to promote the co-operation of voluntary and statutory services and the encouragement of linking together voluntary services

Islington Gazette, September 1970

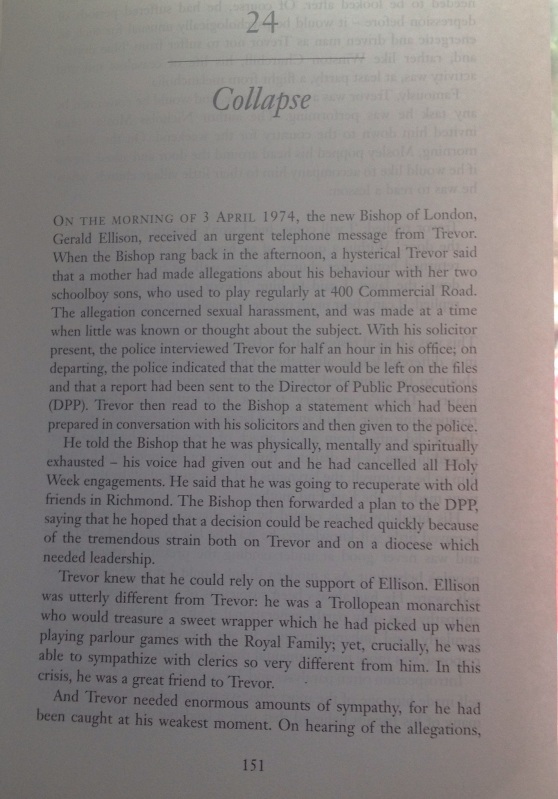

On 3 April 1974 a mother had made allegations that Huddleston had sexually harassed her two schoolage sons. The recently appointed Bishop of London, Gerald Ellison, son of a former royal chaplain and avowed monarchist (in contrast to Huddleston) rallied round. Following an interview with the police in Trevor’s office the police indicated the matter would be left on the files and that a report had been sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions (Sir Norman Skelhorn). Trevor pleaded exhaustion and the Bishop “forwarded a plan to the DPP, saying that he hoped that a decison could be reached quickly because of the tremendous strain both on Trevor and the diocese which needed leadership.”

John Junor of the Sunday Express had sight of the papers prepared by the police and a story was prepared to go to print, with the advice of the Sunday Express legal adviser. However, the Bishop of London got in contact with the Prebendary Dewi Morgan, the rector of St Brides (the beautiful church behind Reuters old HQ on 65 Fleet Street, opposite the majestic black gloss art deco former offices of the Daily Express) who knew Junor through Fleet Street to set up a meeting because “Trevor’s sanity and life were at stake.”

” Junor told Morgan that he had seen the papers and was sure that Trevor was guilty. Later on that day, a version of the story was read out to Dewi Morgan by the Sunday Express legal adviser, the gist of which was intended to scupper trevor’s chances of ever beng promoted to Canterbury. In the event, the story was spiked – much to the relief of Trevor and his friends.” (p.154, Piers McGrandle on Huddleston)

While Trevor recuperated at a friend’s in Richmond, and then to stay at a friend’s holiday house in Scotland, cancelling all engagements until mid-September 1974, things did die down. However, 18 months later Private Eye published on Friday 20 August 1976:

“Sir Robert Mrk has been to see the Bishop of London, Gerald Ellison, over a most delicate matter. It seems that Sir Robert has become concerned over reports from his men about the activities of a certain London churchman. The pillar of the church, who has many coloured immigrants in his diocese, has been engaging in activities of a highly-specilaised, not to say illegal, nature. I will keep you posted about developments.”

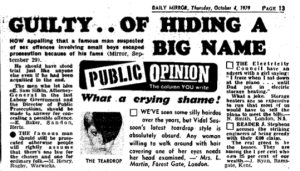

Nothing more was reported until Sir Sam Silkin decided to speak frankly to BBC Radio 4 about the difficulties of prosecuting the famous, which was immediately picked up on by the Daily Mirror’s front page as ‘Famous Mr X and the Law’:

“Silkin was then pursued by reporters from rival papers, asking whether Mr X was not a named politician, whose contacts with the police were chronicled. Silkin denied that the man was Smith and added that he was not an MP at all. But Mr Silkin did add that Mr X ‘was a well-known figure in community work” (p.156 Huddleston) prompting John Junor to write in his column during October:

“Former Attorney General Mr Sam Silkin must have known that he would be unleashing a storm of speculation when he revealed that during his term of office a man prominent in public life had escaped prosecution for sex offences against children because Mr Silkin and the then Director of Public Prosecution had agreed that he was likely to be acquitted – but would have been ruined by court proceedings.

For that could be another way of saying that the prominent man was not necessarily innocent, but that in any court proceedings it would have been his word against the word of the little children and that a jury would almost certainly have accepted his word.

So who was the man? To being with, the rumours centered quite unfairly on a well-known MP. Now it is suggested that he was someone high up in the heirarchy of the Church of England. Mr Silkin may still be unwilling to give name. But, if it were a churchman, should he not be prepared to tell us that in return for non-prosecution he was given an assurance that if the man concerned remained in the priesthood, he would never again be in a position in which he had to deal with children either in England or overseas?”

Interesting to note that Rochdale’s Alternative Press (RAP) publication regarding the allegations against Cyril Smith were actually denied by Silkin as being relevant to Mr X (being Huddleston) – did Silkin make any other reported comments regarding the decision not to prosecute Smith at the time to journalists?

Huddleston’s obituary (written by former Albany Trustee Michael de-la-Noy) for the Independent stated Trevor was moved from Stepney to the Indian Ocean of Mauritius in 1978 to ‘hush up a scandal which will raise a few eyebrows today.”

All the South African intelligence service BOSS’s files on Trevor had been shredded according to Canon Eric James who searched for them when writing his biography of Huddleston during the 1990s.

Cover: Trevor Huddleston by Piers McGrandle (Continuum: London) 2004